Former federal prosecutor and criminal defense attorney Matthew Martens argues in his book “Reforming Criminal Justice: A Christian Proposal” that doing justice is an important way to love God and love our neighbor. He wants us to be better equipped with knowledge and compassion so that we can love our neighbor through pursuing justice. Martens shows us how a biblical system of justice pursues accuracy, due process, impartiality, proper proportionality, and accountability when the system fails (exonerating the innocent and holding bad actors within the system accountable).

From my experience in the church and the legal world, I lament that the church often does a worse job of upholding biblical principles of justice in their ecclesiastical courts than secular courts. Consider the case of Eileen Gray who was disciplined and publicly shamed by her church for leaving her abusive husband and not lifting a restraining order to protect her children. A state court later found Mr. Gray guilty of aggravated child molestation, corporal injury to a child, and child abuse and sentenced him to prison. It is evident that this church misplaced blame on the victim, but to this day, this church has failed to correct this injustice.[i]

Ecclesiastical courts do not “bear the sword” like the state does, but they can play a role in holding wrong-doers accountable and preserving the purity and peace of the church. The proper scope and jurisdiction of ecclesiastical courts could be a separate discussion, but for the purposes of this article we are recognizing that many churches and denominations do practice some form of church discipline and use of church courts. Ideally, church discipline should demonstrate the heart of God for justice while calling sinners to repentance.

Too often, ecclesiastical misjudgments misrepresent God’s good and righteous character and demonstrate a failure to love. It is a travesty of justice when churches fail to act to hold wrongdoers accountable. Even worse is when churches act but discipline the oppressed instead of the oppressor. Worst of all is when oppressive leaders use church courts as a weapon of oppression: to intimidate and punish others, to maintain power and control, and to hide their own wrongdoing.

If we don’t think about how to seek justice in our church courts in our discipline processes until the need arises, we won’t be prepared to deliver justice. We would do well to consider concepts such as due process, the opportunity to be heard, the right to confront our accuser and offer a defense, and the need for witnesses and evidence in our pursuit of truth and justice.

What evidence do we need before we attribute guilt? Too often, we believe false narratives without any evidence and we fail to believe the truth in the face of overwhelming evidence. Ecclesiastical courts should not be a popularity contest between the accuser and the accused. Let us consider the topic of witnesses and evidence and consider the helpfulness of the two-witness principle in Scripture.

The Two-Witness Rule and Its Importance

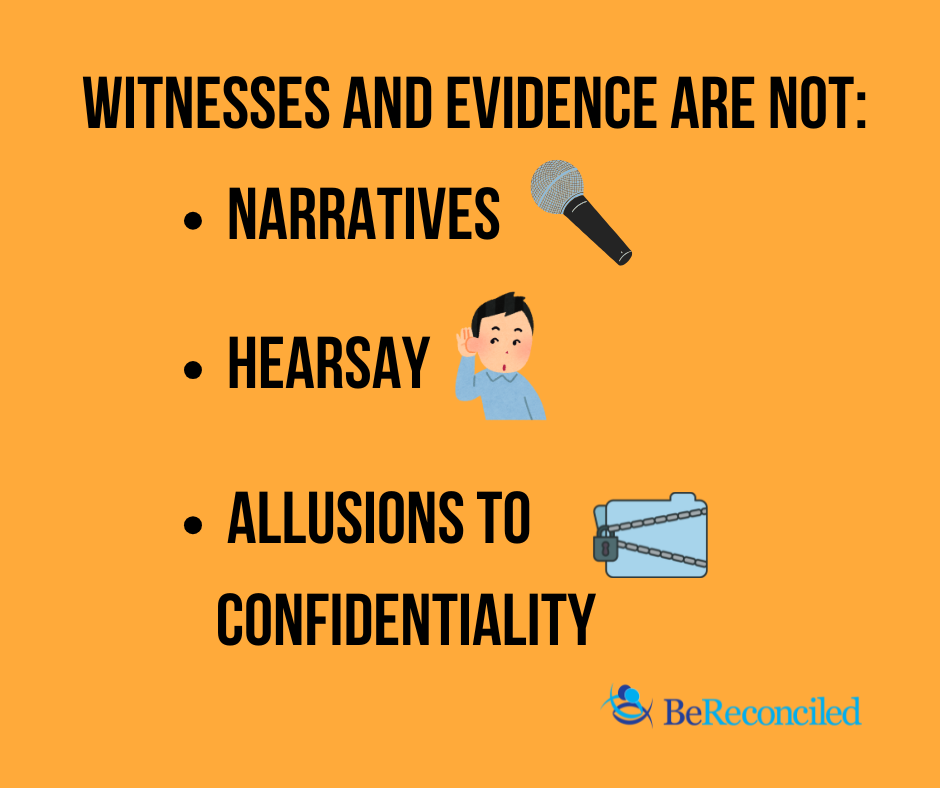

We begin by recognizing that witnesses and evidence are not:

- Narratives: Stories told by those with the biggest platform or loudest voice.

- Hearsay: Someone stating, “Someone else who I can’t name, told me that…”

- Allusions to confidentiality: “If you knew what we knew, you would find this person guilty. But we can’t tell you what we know because of confidentiality.”

Marten highlights how the two-witness rule introduced in the Old Testament is a helpful rule to seek justice in a fallen world. Having more than one witness is a safeguard to the administration of justice. In Deuteronomy it says that one witness is not enough to convict the accused of a crime, rather a matter must be established by the testimony of two or three witnesses. (See Deuteronomy 19:15, Deuteronomy 17:6.)

This rule can be likened to the “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” standard we have in American criminal courts today. Marten argues this rule might let some guilty people go free but “the Israelites would love their neighbors best if they forewent conviction on the testimony of only one witness.”[ii] It would be better that a guilty person go free than an innocent person be wrongly punished.

Marten explains that deciding guilt based on the testimony of one-witness is problematic because it is hard to determine who is lying when there is a he-said or she-said scenario. I would add, we should not assume a person is truthful just because one is in a position of power, whether a police officer, doctor, politician, lawyer, or pastor.[iii] Too often those with charisma or in positions of power control the narrative.

Marten argues, “An evidentiary requirement like the two-witness rule, while a blunt instrument, can serve to enforce the accuracy requirement and protect against overconfidence in our ability, both as witnesses and as judges, to discern the truth from lies.”[iv] Memories are fallible even when there is no malice. The two or three witness rule is helpful to guard against unjust outcomes because of human fallibility or human sin.

While judicial law for Israel is not obliging on us today, the general equity and principles of the Old Testament law give us wisdom for today. Furthermore, the two-witness requirement is repeated in New Testament passages such as Matthew 18:16 and 1 Timothy 5:19 to guide the church. How can the church follow the two-witness principle in its pursuit of accuracy in justice? Who or what counts as a witness?

Who or What Can Count as a Witness?

Wes Bredenhof wrote a blog post entitled, “Who Can Be a Witness, Biblically Speaking?” There he asks us to consider that in sexual abuse cases, the victim may be the only eye-witness to the offense. One may envision a scenario of there being multiple victims accusing one person of wrongdoing but each victim was the sole eye-witness for each separate offense. Does this mean the church can not pursue justice for victims because there are not two or three witnesses to each incident? What if a police officer caught a pastor engaging in indecent extramarital sexual behavior with a parishioner in a public park and the secular courts gave a guilty verdict?[v] Does it matter if the police officer was an atheist?[vi] What evidence does the church need before finding a person guilty?

Do corroborating witnesses count as witnesses? I would argue that corroborating witnesses can serve as witnesses even if they did not see the actual bad act. Wes Bredenhof argues from Leviticus 5:1, stating: “A witness is not only someone who has observed a matter first-hand; he or she can also be someone who has ‘come to know the matter.’ This is the only place in Scripture I am aware of that defines the parameters of what it means to be a witness.”

The “comes to know the matter” witness described in Leviticus 5:1 makes logical sense to me and sounds like a corroborating witness. I recall one of my clients who was sexually assaulted. A police officer’s testimony about observing scratches and bruises on my client’s arms and blood on her pants was an important part of the evidence I wanted the judge to hear. The police officer served as a corroborating witness to verify the truthfulness of my client’s testimony. Perhaps this is how the rape victim in Deuteronomy 22:25-27 receives justice, even though there was no one around to rescue her.

Without a proper understanding of abuse dynamics, we may miss red flags and evidence right before our eyes. We may find a distraught victim before us with a disjointed story that makes little sense to us if we are not familiar with the effects of trauma. (See our Gabby Petito blog post where we highlight how police officers missed red flags for abuse when they interviewed Gabby Petito at a traffic stop days before she was murdered.)

Matthew 18:16 may also be a good argument for corroborative witnesses. Bredenhof explains that a common interpretation of Matthew 18:16 is that the witnesses there are not direct eye-witnesses to the original offense but are there to witness the admonition of the complaint. So if a spouse confronts her husband for adultery, she could bring one or two others to witness the confrontation. (Side note: bringing in others to help in accordance with Matthew 18 or seeking the advice of others is not automatically gossip!) These witnesses to the admonition of a complaint in an interpersonal conflict may become corroborating witnesses as they observe the confrontation and how it unfolds.

Corroborating Evidence and Its Probative Value

In my criminal defense work, I’m thankful for body-cam and dash cam footage to hold both law enforcement and my defendant clients accountable. Dash cam footage has been immensely helpful in resolving disputes over facts. I’ve had police officers drop charges against the accused in multiple cases after they reviewed video footage, whether their own body cam or the defendant’s dash cam footage.

Do DNA evidence, videos, text messages, and emails count as “witnesses”? Yes, corroborating evidence can also serve as a witness. While DNA evidence, videos, emails, and text messages are not technically a second person testifying, these types of evidence may satisfy the principle of accuracy that motivated the two witness rule in its original ancient context. Martens states, “[G]iven technological and scientific advances, there are other evidentiary options that can provide equivalent, and perhaps even greater, reliability than a second eyewitness.”[vii]

In Bible times, they didn’t have the modern technology that we have today. In the account of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38, Tamar presents evidence of Judah’s guilt by revealing his seal, cord, and staff. These items served as corroborating evidence. This weight of evidence was enough for Judah to proclaim that Tamar was more righteous than he was as he exonerated her.

The Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) agrees that corroborative evidence may have probative value in its courts. In the PCA’s Book of Church Order (BCO), it states:

“35-4. The testimony of more than one witness shall be necessary in order to establish any charge; yet if, in addition to the testimony of one witness, corroborative evidence be produced, the offense may be considered to be proved.” – BCO 35:4

This rule in the BCO is helpful in the pursuit of truth and justice. The court weighs the credibility of witnesses and evidence. Naturally, wrong-doers will not want eye-witnesses, corroborating witnesses, or other “corroborative evidence” to even be given a hearing. Yet if we are seeking Biblical justice, we should take care that when a charge is made, there is an opportunity for both sides to be heard and evidence examined.

How Does This Apply to Different Systems of Polity?

How can churches take witnesses and evidence seriously? We should approach examining evidence and witnesses with humility, recognizing our limitations and cognitive biases.[viii] Churches should involve the appropriate civil authorities when dealing with a disclosure of criminal activity.[ix] Even where no criminal violations have been alleged, third party investigations can help with impartiality and help uncover the truth, while respecting the independence of church courts and giving greater clarity.[x]

For churches pursuing censures and excommunications, it is important that church leaders and members understand their role with regards to witnesses and evidence. Those with voting power in church discipline matters need to see the evidence and hear from witnesses to establish a charge. In different forms of church government, we may find that congregants and church leaders may wear different hats when it comes to who is responsible for weighing the evidence and being “the trier of fact”. In many churches, the elders are the ones examining the evidence and are responsible for church discipline, while being held accountable to their office by the congregation. In congregational churches, the whole congregation may have a voting responsibility on church discipline matters. We should ask, “Who needs to be presented with the evidence and who are the triers of fact?”

When applying the authority of the entire church behind a rebuke or call to repentance, churches should understand the importance of due process.[xi] Due process serves an important guardrail in the pursuit of accuracy in verdicts, allowing accusations to be brought and witnesses and evidence to be examined. In our churches, the prosecution needs to make its case, calling witnesses and presenting evidence. Witnesses should be permitted to testify and be cross-examined. Cross-examination is the tool by which the veracity of witnesses is tested.[xii] The accused should be given advanced notice of charges, an opportunity to cross examine witnesses and put on a defense, and given a chance to present his or her own witnesses and evidence.

For those in the PCA, Advocacy from the Presbyterian Pew offers courses about church government and church discipline to help congregants be prepared to love others well while seeking justice. For those in the OPC, the Presbyterian Advocacy Coalition provides advocates to help deal with abuse in the OPC.

Prayer: Let it not be said of us that the Lord despises our assemblies because of unrighteousness and injustice. But let justice roll like a river and righteousness like a never-failing stream! (Amos 5:21-24.)

Questions to think about:

- In court, I hear judges tell juries that a person’s innocence should be considered as important as a person’s guilt. Do you agree with this statement?

- Should church courts be better at pursuing justice and seeking the truth than secular courts? What have you seen in your experience?

- How do we take bearing false witness seriously? Should there be a New Testament era penalty for perjury based on principles from Deut 19:16-21?

- Would it be wrong to remain silent when your testimony can prevent an injustice? (“16 Do not spread lies about anyone, and when someone is on trial for his life, speak out if your testimony can help him. I am the Lord.” – Leviticus 19:16, GNT. See also Martens, pages 77-79.)

[i] Hohn Cho, a faithful elder, tried to get Grace Community Church to correct this injustice. “They sided with a child abuser, who turned out to be a child molester, over a mother desperately trying to protect her three innocent young children. And that was and is flatly wrong, and needs to be made right,” Cho said to CT. “Numerous elders have admitted in various private conversations that ‘mistakes were made’ and that they would make a different decision today knowing what they know now. But those admissions mean you need to make it right with the person you wronged; that is utterly basic Christianity.” – See https://www.christianitytoday.com/2023/02/grace-community-church-elder-biblical-counseling-abuse/.

[ii] Matthew T. Martens, Reforming Criminal Justice: A Christian Proposal (Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway, 2023), 81.

[iii] Diane Langberg writes: “Deception can easily lie below the surface of a high position, great theological knowledge, stunning verbal skills, and excellent performance. As a matter of fact, those are power tools that allow people to live deceptively AND hide the fact that they are doing so.”

[iv] Martens, Reforming Criminal Justice, 82.

[v] These are similar facts surrounding the start of a church discipline case in the PCA. Presbyterian Pew explains that such misconduct from a pastor is not just “an affair” but is Clergy Sexual Abuse. https://presbyterianpew.org/liam-goligher-spiritual-abuse-adult-clergy-sexual-abuse/

[vi] In the PCA, atheists can not be witnesses. There has been debate about the propriety of this rule. See BCO 35:1. https://www.pcaac.org/book-of-church-order/part-2-the-rules-of-discipline/#chapter_35

[vii] Martens, Reforming Criminal Justice, 83-84.

[viii] Statistically, false reports of abuse are rare. For some data on the percentages of false reports in sexual abuse allegations, see this article: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/2012-03/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_False-Reporting.pdf

[ix] Many states have mandatory reporting laws when there is suspected abuse of a minor. For adults, reporting to civil authorities should be a decision of the victim. When there is a report of sexual abuse, rather than encouraging a “we got this” attitude that is resistant to outside help, churches would do well to approach the complexities of sexual abuse with humility and seek outside help. They will need help in interacting with the legal system, working with law enforcement and civil authorities, communicating to the congregation, shepherding victims and offenders, and investigating what happened. Investigations can help a church know how to proceed and uncover the truth.

Section 4 of the PCA’s DASA report states this regarding adult sexual abuse: “Churches are not qualified to conduct investigations of sexual abuse. Local authorities are specifically trained; therefore, if a victim desires the abuse be reported, it must be reported immediately. Delay can result in loss of evidence, victim tampering, tainting witness memory, or providing the perpetrator an opportunity to threaten or pressure their victims to remain silent or recant their testimony. Conducting an “in house” investigation prior to reporting not only jeopardizes the victim and the chain of evidence, it may also fail at detecting the actual abuser. Abusers often continue offending; therefore, a church that conducts an incompetent investigation may be held responsible. The church has a moral and legal obligation to report suspected abuse.” – https://dasacommittee.org/committee-report

[x] “When a church is faced with credible claims of spiritual abuse, the standard practice should be to hire an independent, outside organization that understands how to investigate abuse cases properly…Utilizing outside help does not negate or supersede the proper role of an elder board or presbytery; rather, it simply acknowledges that sometimes churches need expertise they may not be able to provide. The judicial process of a church and the use of an outside organization are not mutually exclusive.” Michael J. Kruger, Bully Pulpit: Confronting the Problem of Spiritual Abuse in the Church (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2022), 127.

[xi] Churches can wrestle with due process concerns such as: How much advanced notice does the accused need before trial to prepare a defense? Should defense counsel be provided for the accused? Who can be a witness? Should witnesses be separated to avoid them hearing each other testify? When and by whom should witnesses be cross-examined? How do we give the accused a right to confront their accusers without unnecessarily traumatizing a victim? Should testimony be recorded and how are the records of the court to be kept? What should we do if new evidence comes to light after trial that may impact a verdict? What is the penalty for perjury? Should there be a right to appeal?

[xii] “Cross-examination serves to draw out whether that witness is sufficiently reliable to satisfy Scripture’s accuracy requirement.” Martens, Reforming Criminal Justice, 104.

In the PCA, BCO 35:7 references cross-examination.